America Is Still in the Heart

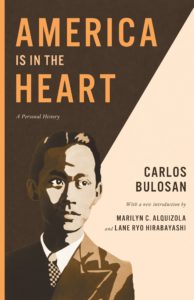

During the time I was reading this book, I was coming back home to the United States after a week-long trip that left a very lasting impact on me. As my plane landed, I pondered heartily on the page I left off on, mid-quote about Carlos Bulosan’s arrival by ship in the United States. I questioned the process of arriving to a place that will someday be “home,” whether that transformation happens by desire or by necessity. This is experience that Carlos Bulosan delves into in his semi-autobiography America Is in the Heart. By telling his own immigrant story, Bulosan exposes a raw look at the hardships he faced after leaving his home in the Philippines and migrating to the United States. Every immigrant had (and perhaps has) the same goal: to achieve the American dream and eventually have a better life in the United States. And although Bulosan went on and became a successful writer later in his life, his early immigrant experience was still a common one–a journey tread by many. Bulosan dealt with pain just as he watched it happen to others. A common thread for immigrants, Bulosan highlights in his book the deep attachment immigrants grow for the United States after they immigrate.

During the time I was reading this book, I was coming back home to the United States after a week-long trip that left a very lasting impact on me. As my plane landed, I pondered heartily on the page I left off on, mid-quote about Carlos Bulosan’s arrival by ship in the United States. I questioned the process of arriving to a place that will someday be “home,” whether that transformation happens by desire or by necessity. This is experience that Carlos Bulosan delves into in his semi-autobiography America Is in the Heart. By telling his own immigrant story, Bulosan exposes a raw look at the hardships he faced after leaving his home in the Philippines and migrating to the United States. Every immigrant had (and perhaps has) the same goal: to achieve the American dream and eventually have a better life in the United States. And although Bulosan went on and became a successful writer later in his life, his early immigrant experience was still a common one–a journey tread by many. Bulosan dealt with pain just as he watched it happen to others. A common thread for immigrants, Bulosan highlights in his book the deep attachment immigrants grow for the United States after they immigrate.

Split into four parts, Bulosan recalls his journey from the Philippines to the United States, from childhood to adulthood. He hails from Binalonan, Philippines, with three brothers and two sisters. As the middle child, he lives a poor life with his parents and his younger siblings, while his older brothers all lead different lives, all leading to the United States eventually and separately. Through his story, Bulosan constantly tries to leave pain behind, but he quickly realizes how haunting his past experiences are. He begins to believe that pain either seems to follow him or is something he cannot leave behind. This attachment to pain becomes a recurring theme in his book, which later takes the form of his feelings towards the United States as a whole. His decision to leave the Philippines, and ultimately his family, is also ignited by a desire to leave his pain behind. His family was in such poverty that he wanted to break free from those struggles at such an early age. Before he even became an adult, he was forced to make the sacrifice to leave his loved ones for the sake of his future. The poverty he faced in the Philippines when he was younger pushed him to leave the country, even if he had no idea of what obstacles were ahead. At the time, Bulosan had one thing in mind: survival. And in his heart was America.

Extending this to the current Filipino American identity, not much has changed. As part of an immigrant race, we have always sought out survival, relying at times on our kinship with other Filipinos in our new homes. The pain of leaving our native country still follows us, regardless of whether that is a direct experience of our own or of our ancestors. As a result, it has made us dream of America even harder. The love that many Filipino Americans have for the United States was born from the pain of leaving the Philippines and the hardships upon arrival in this country. Like Bulosan, we believe that “America is in the hearts of men that died for freedom; it is also in the eyes of men that are building a new world” (189). Because of that, we have mastered standing in the middle of it all, knowing full well that after years of imperialism, racism, and degradation, America is still in our hearts.