Below you can find our compilation of recommended resources on the history of the Chinese in America, the Chinese Exclusion Acts, and connections to contemporary issues of U.S. immigration policy.

Our goal is to provide a curious reader and experienced educators alike with an overview of materials and perspectives as an introduction to the facts and the continued significance of this history.

We hope this section can be dynamic. It is not comprehensive, and we are always learning from our collaborators and fellow educators to be most useful to you. Please contact us with suggestions and questions so we can continue to improve our site. If you are aware of other resources that may be helpful to others, please share them with us at info@1882foundation.org.

An Overview

The Chinese Exclusion Act, a PBS American Experience Documentary by Rick Burns and Li-Shin Yu, thoroughly documents the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Acts, the political resistance to the laws, and the lasting legacy of Exclusion.

Please visit the Center for Asian American Media (CAAM)‘s website for more information on the film, upcoming screenings around the country, and available resources.

Going Deeper

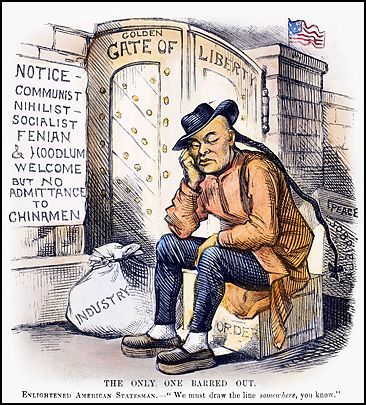

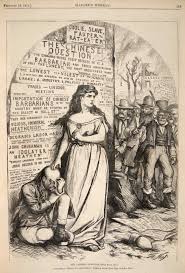

The evidence of anti-Chinese attitudes and actions are pervasive and disturbing reminders of the social side of what led to the passage of and continued to justify Chinese Exclusion. These sources give us a look at the anti-Chinese rhetoric before and during the Exclusion Era that frequently turned violent.

- American Federation of Labor: Some Reasons for the Exclusion of Chinese: Meat vs Rice; American Manhood Against Asiatic Coolieism. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1902.

- This document present the arguments that led to the 1904 law that made Chinese Exclusion permanent.

- Chinese Riot and Massacre: Rock Springs, September 1885

- This primary source reflects an account of the racial animosity and violence present across Western mining towns.

- “Chinese Laborers Meet Resistance in the Washington Territory.” HistoryNet. June 12, 2006.

- This article describes with great detail the mob violence and anti-Chinese sentiment in the American West.

- CINARC: Anti-Chinese Violence in the Pacific Northwest

- The Chinese in Northwest American Research Committee (CINARC) has gathered several helpful resources on their website.

- Driven Out: The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans. By Jean Pfaelzer. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008.

- Pfaelzer’s book provides valuable perspectives on the racial violence inflicted on Chinese communities in the late 19th century.

- Harper’s Weekly: Anti-Chinese Riots

- A popular illustrated magazine reports on anti-Chinese violence in Seattle in 1886.

- National Archives: 1884 Labor Unions’ Boycott of Chinese Businesses

- Anti-Chinese sentiment didn’t always take the force of racial violence. This review from the National Archives provides valuable context of other anti-Chinese tactics of the late 19th century.

- The Society Pages: Yellow Peril” Posters and Cartoons from the Chinese Exclusion Period

- Visual representations of anti-Chinese sentiment provide disturbing reminders of the tone with which anti-Chinese attitudes were perpetuated and shared across the country to a mainstream audience.

The resources below highlight the complexities and contradictions of the enforcement of the Chinese Exclusion Laws.

- Calavita, Kitty. (2000). The Paradoxes of Race, Class, Identity, and “Passing”: Enforcing the Chinese Exclusion Acts, 1882-1910. Law & Social Inquiry, 25(1), 1–40.

- Calavita expertly examines the contradictions and chaos of the enforcement of the Chinese Exclusion Laws on the ground, not only, she argues, due to the vague instruction put forward by the policy, but also because of the “paradoxes associated with prevailing assumptions about race, class, and identity more generally” (page 2). The article also includes a fascinating discussion of the significance of Chinese American resistance and subversion of the laws, which further exacerbated the failings of enforcement of each new policy.

- Lee, Erika. At America’s gates: Chinese Immigration During the Exclusion Era, 1882-1943. The University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

- Lee’s book provides incredible detail on the enforcement of Exclusion and the Chinese resistance to the policies, including discussion of the “paper son system.”

- National Archives: Federal Agencies’ Enforcement of the Chinese Exclusion Laws

- The National Archives provide a concise overview of the government entities responsible for enforcement, as well as direction on where/how to access original case files and court records.

- National Archives: Records of Chinese Persons Passing Through San Francisco and Honolulu During the Chinese Exclusion Period

- The National Archives highlights the significance of Angel Island Immigration Station (1910-1940) as a site of enforcement of Chinese Exclusion

- Pegler-Gordon, Anna. In Sight of America: Photography and the Development of U.S. Immigration Policy. University of California Press, 2009.

- Pegler-Gordon explores the subjectivity of enforcement of the Geary Act (1892) of the Chinese Exclusion Acts, requiring photographic identification for only Chinese in the U.S. She critically also examines photography as a means for the Chinese to resist Exclusion through subversive measures.

- Washington (Territory), and Watson C. Squire. Report of the Governor of Washington Territory to the Secretary of the Interior, 1886. Washington: G.P.O., 1886.

- The Governor of Washington describes the challenges of enforcing the Chinese Exclusion Act, while also weighing the tensions over the need for labor and his perceptions of the challenges of Chinese populations in the Pacific Northwest.

The timeline below provides a chronological overview of U.S. legal policies and decisions that both directly and indirectly affected Chinese immigration to the United States.

- 1790 Naturalization Act: Allowed only “free white person[s]” to become American citizens. Text

- 1870 Naturalization Act: Although Congress amended the naturalization laws to allow persons of African descent to become naturalized American citizens, the Senate explicitly rejected an amendment to extend naturalization to persons of Chinese descent.

- 1875: The Page Act prohibits “undesirable” persons defined as “forced laborers” convicts, and anyone from “China, Japan, or any Oriental country” engaged in “lewd and immoral purpose” and prohibits Asian women immigrating “for the purpose of prostitution.” It is applied severely and almost exclusively against Chinese women. Text

- 1879 “15 Passenger Bill”: Congress restricted Chinese immigration by limiting the number of Chinese passengers permitted on any ship coming to the U.S. to 15. Leaders in the Congressional debate expressed the view that Chinese persons were “aliens, not to be trusted with political rights.” President Rutherford B. Hayes vetoed the bill as being inconsistent with U.S.-China treaty commitments that permitted the free movement of peoples.

- 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act (20 Year): Congress suspended the immigration of skilled and unskilled Chinese laborers for twenty years, and expressly prohibited state and federal courts from naturalizing Chinese persons. President Chester A. Arthur vetoed this bill for being incompatible with U.S.-China treaty obligations.

- 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act (10 Year): In light of President Arthur’s veto of the 20 year ban, Congress revised the Chinese Exclusion Act to impose a ten year ban on the immigration of Chinese laborers. Congress kept in place the provision expressly prohibiting courts from naturalizing Chinese persons. The new act mandated that certain Chinese laborers wishing to reenter the U.S. obtain “certificates of return.” This was the first federal law excluding a single group of people from the United States on the basis of race or ethnicity alone. Text

- 1884: The Exclusion Law Amendments broadened the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 to apply to all persons of Chinese descent, “whether subject of China or any other foreign power.” The amendments also imposed stricter documentation requirements on travel for persons of Chinese descent.

- 1888: The Scott Act prohibited all Chinese laborers who left the United States, or who in the future would choose to leave, from reentering. The Scott Act canceled all previously issued “certificates of return,” meaning that 20,000 Chinese laborers then overseas who held these certificates could not return to the United States. The Supreme Court recognized that the act abrogated U.S.-China treaty obligations, but nonetheless upheld the act’s validity, reasoning that Congress had absolute authority to exclude aliens. Text

- 1892: The Geary Act extends all previous Chinese Exclusion Laws by ten years. By requiring Chinese persons in the United States to carry a “certificate of residence” at all times, the Geary Act made Chinese persons who could not produce these certificates presumptively deportable unless they could establish residence through the testimony of “at least one credible white witness.” Congress also denied bail to Chinese immigrants who applied for writs of habeas corpus. Text

- 1898: Wong Kim Ark vs. United States establishes legal precedent to ensure that the 14th Amendment extends birthright citizenship to all children born on U.S. soil, regardless of his or her parents’ eligibility for U.S. citizenship. In the context of the Chinese Exclusion laws, this decision critically secured citizenship rights to Chinese Americans and enabled the community to resist the policies . Text

- 1902: Congress indefinitely extended all Chinese Exclusion Laws. Text

- 1904: Congress made permanent all Chinese Exclusion Laws. Reference

- 1917: “Asiatic Barred Zone Act” is passed amidst the turmoil and chaos of U.S. involvement in WWI. The act heightened literacy requirements for all immigrants and excluded all migrants from “any country not owned by the U.S. adjacent to the continent of Asia” (emphasis added). This carved out exceptions for U.S. imperial ambitions in Southeast Asia and the Pacific, but specifically broadened the exclusion of all other Asian people. Text

- 1924: The Immigration Act of 1924 (Johnson-Reed Act) establishes an annual quota system by national origins. The quotas were based off of the population in the United States according to the 1890 census and prohibited immigration of people “ineligible to become citizens” (reinforcing the “Asiatic Zone of Exclusion.”) Text

- 1943: The Magnuson Act repealed all laws “relating to the exclusion and deportation of the Chinese.” Congress permitted 105 persons of Chinese descent to immigrate into the United States each year, and enabled persons of Chinese descent to become American citizens. The 1943 repeal, however, was enacted a wartime measure to counteract enemy propaganda after China became an ally of the United States during World War II, with little acknowledgment of the injustice of the laws. Text

- 1945-1946: The War Brides Act is passed in a series of laws to enable American WWII veterans to bring their spouses and children to United States, despite immigration quotas based on national origin. The first of these laws, however, did not apply to Chinese until revisions were made almost two years after the first War Brides Act to provisions of the immigration law that continued to restrict Chinese immigration. Text

- 1952 – Walter-McCarran Act consolidates and reforms the laws governing immigration the United States. While still maintaining quota restrictions based on national origin, the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act begins to weaken immigrant selection solely on national origin, creating space for migration from communist countries in the context of the Cold War. Text

- 1965: The Hart-Celler Immigration Act abolishes the quota system based on national origins. Prioritizing family reunification, the law’s proponents predicted the policy would have little effect on the scale and composition of immigration to the US. Against their predictions, the Hart-Cellar Act greatly diversified and rapidly increased immigration in a way that had been legally restricted since the sweeping passage of Johnson-Reed in 1924. Additional Background.

- 2011 – 2012 – U.S. Senate and House of Representatives separately pass unanimous resolutions condemning the Chinese exclusion laws, expressing regrets, and reaffirming Congress’s responsibility to protect the civil rights of all people in the United States. The 1882 Foundation is proud to have partnered with other organizations and representative to secret this statement of regret. Additional Background

Many contemporary journalists and scholars are engaging with the history of Chinese Exclusion to connect with Asian American identity today, and also critique immigration policy affects other immigrant groups. National public rhetoric and sentiment share striking similarities to that of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Below, we included select articles that we find helpful when linking past and present.

Chow, Kat. “As Chinese Exclusion Act Turns 135, Experts Point To Parallels Today.” Code Switch: Race and Identity, Remixed. NPR. May 5, 2017.

- On the anniversary of the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, Chow engages with Dr. Erika Lee to make connections with anti-immigrant sentiment in the 21st century.

Hsu, Irene. “The Echoes of Chinese Exclusion: How U.S. Immigration Policy Uprooted Chinese American Communities — with effects that are still felt today.” The New Republic. June 28, 2018.

- Hsu makes the critical link between the need for Chinese labor to complete the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 and the racial tensions over labor that contributed to the passage of Exclusion. She links American economic and commercial expansion and white nationalism, arguing their historic compatibility that informs contemporary politics.

Lee, Erika. (2002). The Chinese Exclusion Example: Race, Immigration, and American Gatekeeping, 1882-1924. Journal of American Ethnic History, 21(3), 36–62.

- In this article, Lee connects the enforcement of the Chinese Exclusion Act and racialization of Chinese immigrants to the creation of a “gatekeeping ideology” that persists in the exclusion of other immigrant groups today (page 38).

We hope our readers will continue to share resources that inform your own research or community history. We have included other citations below that have informed some of our previous work on studying this history.

Other Digital Resources

- Becoming American: The Chinese American Experience

- A PBS page of digital resources, oral histories, and program summaries.

- Harpers Weekly: The Chinese-American Experience, 1857-1892

- A reflection on Harpers Weekly as a publication and its role both challenging and perpetuating anti-Chinese sentiment in the 19th century.

Books and Articles

- Ahmad, Diana L. The Opium Debate and Chinese Exclusion Laws in the Nineteenth Century American West. Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2007.

- Bagley, Clarence B. History of Seattle, From the Earliest Settlement to the Present Time. Chicago, S. J. Clarke, 1916 Volume II, Chapter XXV, The Anti-Chinese Agitation and Riots, pp. 455-478.

- Chan, Sucheng (ed.) Entry Denied: Exclusion and the Chinese Community in America, 1882 – 1943. 1991.

- Chang, Iris. The Chinese in America: A Narrative History. New York: Viking, 2003.

- Chin, Art. Golden Tassels: A history of the Chinese in Washington. 1977.

- Chin, Doug. Seattle’s International District: The Making of a Pan-Asian American Community. Seattle: International Examiner Press, 2009.

- Chin, Doug and Art Chin. Up Hill: The Settlement and Diffusion of the Chinese in Seattle. Seattle: Shorey Book Store, 1973.

- Cowan, Robert Ernest and Boutwell Dunlap. Bibliography of the Chinese Question in the United States. San Francisco: A. M. Robertson, 1909.

- Daniels, Roger. Asian America: Chinese and Japanese in the United States Since 1850. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988.

- Dirlik, Arlif (editor). Chinese on the American Frontier. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2001.

- Dunn, Ashley. “Seattle’s Chinese Expulsion,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 4 February 1986.

- Gold, Martin B, Forbidden Citizens – Chinese Exclusion and the U.S. Congress: A Legislative History, Capitol.net, 2012.

- Gyory, Andrew. Closing the Gate: Race, Politics and the Chinese Exclusion Act. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

- Halsreth, James A. and Bruce A Glasrud. “Anti-Chinese Movements in Washington, 1885 – 1886: A Reconsideration” in Halsreth and Glasrud (eds.) Northwest Mosaic, Pruett Publishing Co., 1977.

- Hildebrand, Lorraine. Straw Hats, Sandals, and Steel: The Chinese in Washington State. Ethnic history series, 2. Tacoma: Washington State American Revolution Bicentennial Commission, 1977.

- Hsu, Madeline Yuan-yin. Dreaming of Gold, Dreaming of Home: Transnationalism and Migrations between the United States and South China 1882-1943. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000.

- Hunt, Herbert. Tacoma, Its History and Its Builders; a Half Century of Activity. Chicago: S.J. Clarke Pub. Co, 1916; Chapter 32: The Chinese Menace.

- Karlin, Jules Alexander. “The Anti-Chinese Outbreaks in Seattle, 1885-1886.” Pacific Northwest Quarterly, April, 1948. pp. 103-130.

- Kinnear, George. Anti-Chinese Riots in Seattle, Wn., February 8th, 1886.Seattle: Self-published, 1911.

- Lee, Erika and Judy Yung. Angel Island: Immigrant Gateway to America. Oxford University Press, 2010.

- McClain, Charles J. In Search of Equality: The Chinese Struggle Against Discrimination in Nineteenth-Century America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

- Morgan, Murray. Puget’s Sound: A Narrative of Early Tacoma and the Southern Sound. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003.

- Ngai, Mae. Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton University Press, 2004.

- Roth, Lottie Roeder. History of Whatcom County. Chicago: Pioneer Historical Pub. Co, 1926.

- Saxton, Alexander. The Indispensable Enemy: Labor and Anti-Chinese Movement in California. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

- Schwantes, Carlos A. Radical Heritage: Labor, Socialism and Reform in Washington and British Columbia, 1885-1917. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1979.

- Taylor, Quintard. The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District, from 1870 Through the Civil Rights Era. The Emil and Kathleen Sick lecture-book series in western history and biography. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994; Chapter 4: Blacks and Asians in a White City, 106-134.

- Wilcox, W.P. “Anti-Chinese Riots in Washington,” Washington Historical Quarterly, Vol 20 No 3 (20 July 1929), 204-12.

- Wong, K. Scott and Sucheng Chan (editors). Claiming America: Constructing Chinese American Identities during the Exclusion Era. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998.

- Wu, Cheng-Tzu. “Chink!” A Documentary History of Anti-Chinese Prejudice in America. New York: World Publishing, 1972.

- Wynne, Robert Edward. Reaction to the Chinese in the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia, 1850-1910. New York: Arno Press, 1978.