Transcontinental Railroad & Summit Tunnel

From 1865 to 1869, Chinese railroad workers built the Transcontinental Railroad through the Sierra Nevada mountains. Approximately 12,000-20,000 Chinese railroad men making up to 90 percent of the Central Pacific Railroad workforce risked life and limb to cut and build railroad bed and dig tunnels in the most difficult and perilous terrain and weather of the entire Transcontinental Railroad project. The accomplishments of the Chinese railroad workers were a key contribution to the rapid economic development of the American west and the entire American economy. In 2014 Secretary of Labor, Tom Perez, at the ceremony that inducted the Chinese railroad workers into the Department of Labor Hall of Honor, liken this contribution to the creation of the internet in the way it transformed the US economy for decades into the future.

It is impossible to speak of the Transcontinental Railroad as a “great project” without erasing the histories of violence against marginalized communities which allowed the railroad to be completed. Not only were Chinese workers often subjected to horrific working conditions and severe labor exploitation, but the railroad’s construction further enabled the violent displacement and colonization of thousands of Indigenous tribes who previously inhabited the West Coast. To claim that the Transcontinental Railroad was a uniformly great project is to sanitize and minimize these histories — not only of the exploitation to which Chinese laborers were subjected, but of the violence against Native Americans that enabled the railroad’s completion.

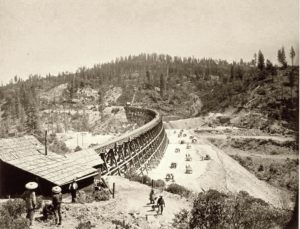

Central Pacific Railroad (CPR) began work on the western portion of the Transcontinental Railroad in Sacramento on January 8, 1863. They encountered their first significant obstacle in spring of 1864: a long, tall ridge at Bloomer Ranch. This ridge, which was made of a rock suspended in clay, effectively formed a massive, natural concrete wall. Workers broke picks, shovels, and other equipment attempting to break through the ridge, and eventually resorted to using black blasting powder. Using 500 kegs of explosives per day, the crew began chipping away at the ridge.

Central Pacific Railroad (CPR) began work on the western portion of the Transcontinental Railroad in Sacramento on January 8, 1863. They encountered their first significant obstacle in spring of 1864: a long, tall ridge at Bloomer Ranch. This ridge, which was made of a rock suspended in clay, effectively formed a massive, natural concrete wall. Workers broke picks, shovels, and other equipment attempting to break through the ridge, and eventually resorted to using black blasting powder. Using 500 kegs of explosives per day, the crew began chipping away at the ridge.

The work was incredibly dangerous. One explosion blinded the left eye of the energetic and tall foreman, Harvey Strobridge after he attempted to prepare 50 pounds of powder. The Chinese respected Strobridge, and those who learned English called him “Stro” or the “One-eyed bossy man.” Strobridge respected the Chinese workers after working a month with them. He stated, “They learn quickly, do not fight, have no strikes that amount to anything, and are very cleanly in their habits. They will gamble and do quarrel among themselves most noisily – but harmlessly.” The chief engineer, Samuel Montague, stated “The Chinese are faithful and industrious and under proper supervision soon become skillful in the performance of their duty. Many of them are becoming experts in drilling, blasting, and other departments of rock work.”

The work was incredibly dangerous. One explosion blinded the left eye of the energetic and tall foreman, Harvey Strobridge after he attempted to prepare 50 pounds of powder. The Chinese respected Strobridge, and those who learned English called him “Stro” or the “One-eyed bossy man.” Strobridge respected the Chinese workers after working a month with them. He stated, “They learn quickly, do not fight, have no strikes that amount to anything, and are very cleanly in their habits. They will gamble and do quarrel among themselves most noisily – but harmlessly.” The chief engineer, Samuel Montague, stated “The Chinese are faithful and industrious and under proper supervision soon become skillful in the performance of their duty. Many of them are becoming experts in drilling, blasting, and other departments of rock work.”

Ultimately, workers removed over 40,000 cubic yards of material, completing the grade and tracks through Bloomer Cut in the spring of 1865. The first train reached Auburn from Sacramento on May 13, 1865, and Bloomer Cut was considered a great engineering feat to merit the title of the “Eighth Wonder of the World.” The concrete-like walls have preserved Bloomer Cut well, and the site today still looks much the same as it did in 1865.

Ultimately, workers removed over 40,000 cubic yards of material, completing the grade and tracks through Bloomer Cut in the spring of 1865. The first train reached Auburn from Sacramento on May 13, 1865, and Bloomer Cut was considered a great engineering feat to merit the title of the “Eighth Wonder of the World.” The concrete-like walls have preserved Bloomer Cut well, and the site today still looks much the same as it did in 1865.

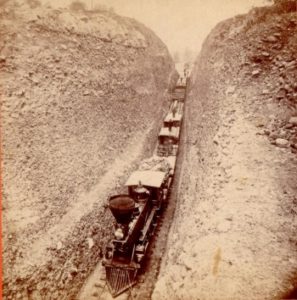

Ships and travelers sailed around the legendary Cape Horn near the southern tip of South America as a main colonial trading route between the 1600’s and early 1900’s. Inspired by the earlier colonizers, gold seekers who helped build the Transcontinental Railroad decided to name a section of railroad passage “Cape Horn,” around a rocky outcrop 1300 feet above the north fork of the American River. The Cape Horn passage posed the greatest challenge for the crew, forcing them to lay tracks around a steep mountainside. Most engineers considered the idea preposterous, but Central Pacific completed the job with the help of Chinese workers.

Ships and travelers sailed around the legendary Cape Horn near the southern tip of South America as a main colonial trading route between the 1600’s and early 1900’s. Inspired by the earlier colonizers, gold seekers who helped build the Transcontinental Railroad decided to name a section of railroad passage “Cape Horn,” around a rocky outcrop 1300 feet above the north fork of the American River. The Cape Horn passage posed the greatest challenge for the crew, forcing them to lay tracks around a steep mountainside. Most engineers considered the idea preposterous, but Central Pacific completed the job with the help of Chinese workers.

In summer 1865, Chinese workers began side hill rock cutting. To begin establishing the railroad bed on the side of the mountain, Chinese workers were likely lowered by rope down to the level of the planned roadbed until they were able to excavate a foothold through pick, shovel, or explosives.

Clearing the railroad bed was difficult, time consuming, and dangerous. Rocks, large trees, stumps, and other vegetation needed to be removed. When using , the explosion sent piecesof rocks, trees, and soil flying through the air at high velocity, which often accidentally killed Chinese workers.

While visiting the Colfax area, one reporter wrote about Chinese workers: “They were a great army laying siege to Nature in her strongest citadel. The rugged mountains looked like stupendous ant-hills. They swarmed with Celestials, shoveling, wheeling, carting, drilling and blasting rocks and earth…” Ultimately, Chinese workers finished excavating the railroad bed and laying the tracks during the spring 1866. The route eventually became popular with travelers because of the panoramic view from Cape Horn; trains often stopped at Cape Horn to allow passengers to appreciate the view.

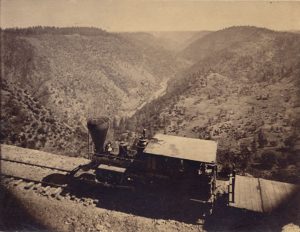

The miners who discovered gold in this area wanted to keep the location a secret, and thus founded Secret Town. At the time, the Transcontinental Railroad ran near Secret Town as an impressive wooden trestle that stretched 1,110 feet across and 95 feet above a nearby ravine. The wooden trestles, however, often caught fire from smokestack sparks as trains crossed. To solve this dilemma, the Central Pacific Railroad hired Chinese laborers to fill the Secret Town trestle with dirt.

Chinese laborers moved large volumes of dirt from the surrounding landscape with hand and mule carts to the trestle. The subsequent filling of Secret Town ravine to accommodate I-80 and other features have largely minimized the scale of the Chinese laborers’ accomplishments.Today, the trestle remains buried under the fill.

Building the railroad through the Sierra Nevada was the most challenging aspect of the Transcontinental Railroad. Chinese laborers had to initially bore through rock using 8-pound sledge hammers and chisels, often by candle light or lantern, to create 2-feet deep by 2.5-inch wide holes, which took hours for a 3-man crew to create. The Chinese laborers first filled 1/3 of the hole with blasting powder, and then clay/hay/sand to secure the fuse. They lit the fuse, ran, and the subsequent explosion sent rock debris, dust, and black powder residue into the air, which made breathing difficult.

Building the railroad through the Sierra Nevada was the most challenging aspect of the Transcontinental Railroad. Chinese laborers had to initially bore through rock using 8-pound sledge hammers and chisels, often by candle light or lantern, to create 2-feet deep by 2.5-inch wide holes, which took hours for a 3-man crew to create. The Chinese laborers first filled 1/3 of the hole with blasting powder, and then clay/hay/sand to secure the fuse. They lit the fuse, ran, and the subsequent explosion sent rock debris, dust, and black powder residue into the air, which made breathing difficult.

Aside from the dangerous blasting, many more Chinese men lost their lives during the harsh winters. During the winter of 1866-1867, there were 44 storms, many of which dumped over 6 feet of snow. Avalanches frequently swept groups of Chinese workers to their deaths. Chinese laborers had to resort to working and traveling through the snow in excavated snow rooms and snow tunnels connecting where they worked to where they lived in their bitterly cold one- and two-story wooden buildings.

Aside from the dangerous blasting, many more Chinese men lost their lives during the harsh winters. During the winter of 1866-1867, there were 44 storms, many of which dumped over 6 feet of snow. Avalanches frequently swept groups of Chinese workers to their deaths. Chinese laborers had to resort to working and traveling through the snow in excavated snow rooms and snow tunnels connecting where they worked to where they lived in their bitterly cold one- and two-story wooden buildings.

Summit Camp, where those structures were located, remains one of the longest-standing camps from the railroad construction era. Despite the harsh working conditions, Chinese laborers were not treated equally to their fellow white workers. On June 25th, around 5,000 Chinese went on a strike against the Central Pacific Railroad. The strike took place along the eastern slope of the Sierras between Cisco and Strong’s Canyon, which is near nowaday Eder. Chinese laborers fought for their rights including a pay increase, reduced workdays, and shorter shifts drilling in life threatening tunnels.

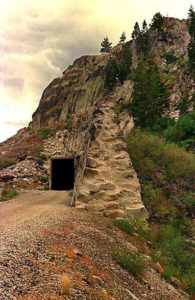

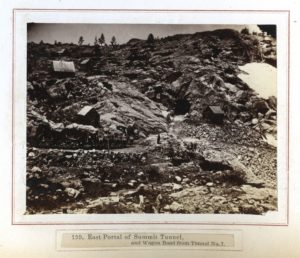

In retaliation, the director of Central Pacific Railroad Charles Croker cut off food and supply trains, even threatening violence against those workers. After eight days, the workers ultimately ended their strike without any of their demands being met. Later evidence, however, suggests that they did receive a pay raise several months later.After beginning work in the Sierras in the fall of 1865, Chinese laborers laid the tracks through the most difficult of the 1,687-feet Summit Tunnel #6 on November 30, 1867. Eventually, they built 37 miles of snow sheds through the Sierra Nevada by 1869. As snow removal techniques improved, many of the older wooden snow sheds grew unnecessary, and were later removed. Those that were still needed were eventually replaced by concrete snow sheds, which remain on site today.

When Chinese laborers worked on the First Transcontinental Railroad in Sierra Nevada mountains, they also built work camps along the railroad line. As construction progressed, these Chinese workers kept moving east, so most of the eastward camps consist of temporary structures. Summit Camp, however, is different from most of these work camps. Located just above the east entrance to the Summit Tunnel (Tunnel #6), this camp was in use during the construction of the Summit Tunnel in 1865 and was continually used until 1869 long after the tunnel’s completion in 1867. Due to its longer operation time along with the harsh winters on Donner Summit, Summit Camp has more substantial structures. The one- and two-story high houses in Summit Campwere built to endure heavy snow to protect Chinese workers.

Still, working conditions were difficult. Many workers could barely see the sun in winter as they traveled back and forth between their houses and tunnels under the snow for months. It is highly possible that when Summit Camp was abandoned, the buildings were deconstructed and reused elsewhere. Over the years, archaeologists have found many historic objects depicting the life of Summit Camp’s Chinese inhabitants, including coins, porcelain rice bowls, and opium pipe bowls. However, efforts to preserve the historic site have been challenged by ongoing construction and increased tourist activity.

Still, working conditions were difficult. Many workers could barely see the sun in winter as they traveled back and forth between their houses and tunnels under the snow for months. It is highly possible that when Summit Camp was abandoned, the buildings were deconstructed and reused elsewhere. Over the years, archaeologists have found many historic objects depicting the life of Summit Camp’s Chinese inhabitants, including coins, porcelain rice bowls, and opium pipe bowls. However, efforts to preserve the historic site have been challenged by ongoing construction and increased tourist activity.

More than 150 years after its original construction,, a stone wall, originally built to hold up parts of the railroad tracks, still stands at Donner Summit between tunnels #7 and #8 . This railroad retaining wall is called China Wall or Chinese Wall to commemorate the contributions of Chinese laborers whose labor allowed for the completion of railroad work in the Sierra mountains. On August 11th, 1984, the Truckee-Donner Historical Society marked this place as a historic landmark with a plaque telling the story of Chinese Railroad Workers.

More than 150 years after its original construction,, a stone wall, originally built to hold up parts of the railroad tracks, still stands at Donner Summit between tunnels #7 and #8 . This railroad retaining wall is called China Wall or Chinese Wall to commemorate the contributions of Chinese laborers whose labor allowed for the completion of railroad work in the Sierra mountains. On August 11th, 1984, the Truckee-Donner Historical Society marked this place as a historic landmark with a plaque telling the story of Chinese Railroad Workers.

Known locally as “Catfish Pond,” this green pool of water at the top of Donner Pass in the Tahoe National Forest is home to dozens of small, whiskered catfish. Catfish are not native to the Sierras; nor are they naturally found at such high elevation (approximately 7,000 ft.). This pond has no streams that feed into it. Therefore, it is thought that this pond was stocked with catfish in the late 1860’s to feed Chinese workers, who were building a stretch of the Transcontinental Railroad nearby. The descendants of these stocked fish have survived in the pristine pond for more than 150 years and continue to thrive in this unusual environment, even as the pond is covered with around ten feet of snow each winter.

Known locally as “Catfish Pond,” this green pool of water at the top of Donner Pass in the Tahoe National Forest is home to dozens of small, whiskered catfish. Catfish are not native to the Sierras; nor are they naturally found at such high elevation (approximately 7,000 ft.). This pond has no streams that feed into it. Therefore, it is thought that this pond was stocked with catfish in the late 1860’s to feed Chinese workers, who were building a stretch of the Transcontinental Railroad nearby. The descendants of these stocked fish have survived in the pristine pond for more than 150 years and continue to thrive in this unusual environment, even as the pond is covered with around ten feet of snow each winter.

At places like catfish pond, Chinese railroad workers began to adapt parts of their rich and varied food culture to a strange, foreign land. While other workers drank water from communal dippers, Chinese laborers preferred to drink tea and hot water, reducing incidences of dysentery and other illness-causing microbes that were killed during the boiling process. They preferred to eat Chinese foods, including dried fish, dried vegetables, dried oysters and rice. The Central Pacific Railroad gave exclusive rights to Sisson, Wallace and Company, to provide food and other provisions to the railroad workers. As the railroad tracks gradually extended through the Sierra Nevada’s, a train car labeled “China Store” followed the work camps to the end of the tracks so that Chinese workers could make purchases. In groups of 12 to 30 men, crews could pay for a Chinese cook to prepare their meals. These cooks were highly valued and often compensated far better than the laborers they were feeding.

At places like catfish pond, Chinese railroad workers began to adapt parts of their rich and varied food culture to a strange, foreign land. While other workers drank water from communal dippers, Chinese laborers preferred to drink tea and hot water, reducing incidences of dysentery and other illness-causing microbes that were killed during the boiling process. They preferred to eat Chinese foods, including dried fish, dried vegetables, dried oysters and rice. The Central Pacific Railroad gave exclusive rights to Sisson, Wallace and Company, to provide food and other provisions to the railroad workers. As the railroad tracks gradually extended through the Sierra Nevada’s, a train car labeled “China Store” followed the work camps to the end of the tracks so that Chinese workers could make purchases. In groups of 12 to 30 men, crews could pay for a Chinese cook to prepare their meals. These cooks were highly valued and often compensated far better than the laborers they were feeding.