D.C. Chinatown Walking Tour

Explore the tour below, and keep an eye out for in-person guided tours in the future.

Location: 6th and Eye Street, in front of the Moy Family Association

D.C. Chinatown’s history begins in the 1800’s, and is generally considered by the presence of Chinese people appearing in records, in writing, and in the public eye, but the marginalized status early Chinese immigrants in the U.S.

In 1851, the first Chinese person would register an address on Pennsylvania Avenue. His name was Chiang Kai. The majority of the first residents were new immigrants, seeking to settle in urban centers where working-class jobs would be widely available. Some early residents were also from the West Coast, escaping Sinophobic conditions developed under retaliation by American workers against cheap Chinese labor, which had been driven to the area by an economic boom fueled by the Gold Rush (1848-1855). These residents took up small business jobs in restaurants, grocery stores, dry cleaners, and many more, due to exclusion from other white-dominated trades. By 1884, the population was estimated at around 100 individuals.

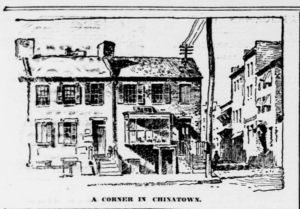

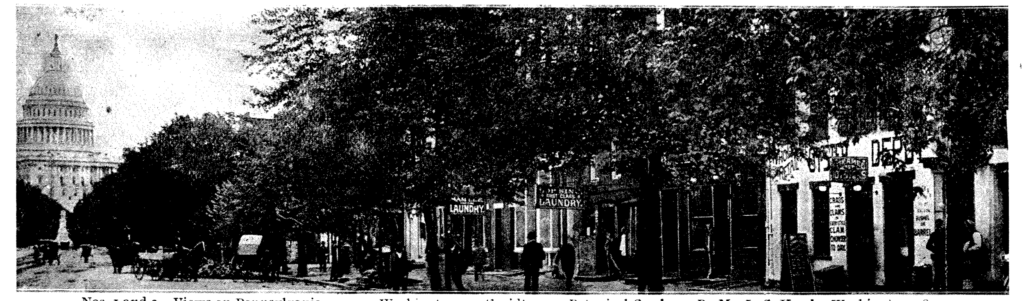

This population would remain stunted as racism towards Asian immigrants, particularly Chinese, worsened. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 dictated that no Chinese nationals were to be allowed to enter the country, and those already in the U.S. were barred from citizenship, further contributing to their alienation. The population is primarily made of bachelors, as many originally immigrated with plans to bring their families after having settled. By 1903, Chinatown had established itself as an insular and functional community. The Evening Sun described the neighborhood as “where the real Chinese life is to be found.” Social networks from villages in China allowed new immigrants, mainly from Southern China’s Taishan area, to seek the familiar in an unfamiliar place. Connections from ancestral homes often carried into the new locale, and were significant enough that a single contact from China served as justification for immigrants choosing the new American soil they chose to make their new lives. By 1928, the Chinese population of Washington D.C. was estimated at around 600. At its peak, the neighborhood occupied the south side of Pennsylvania Avenue, stretching from 2nd to 4 ½ Street.

The reaction of the wider public to the blossoming community was largely negative, with the residents considered dirty, secretive, mysterious, and highly insular. Many outside the enclave actively worked to suppress Chinese presence by buying out real estate, discriminatory hiring practices, and actively racist rhetoric, further confining the community. For example, stereotypes persisted that Chinese had an affinity and particular talent for doing laundry, while in fact it was racist hiring practices that demanded that immigrants own and operate their own businesses. The April 2nd, 1903 issue of the Evening Star, speaking on the classic American Chinese dish chop suey, read:

“The Americanized celestial looks invariably pale, and in most instances half fed, and people think of a Chinaman as scrubbing away in his laundry day and night, and subsisting on rice, but it is said that this wan, pallid fellow, with his funny hat and combination cape, sacque, and petticoat, is about the merriest and best ordered glutton to be found on a day’s journey.”

Fear existed that a phenomenon was underway in D.C. as was happening in the West Coast, where inexpensive Chinese labor left many white laborers without jobs. Because of this discrimination, the early Chinatown community was shaped heavily by internally-adjudicated organizational structures. Family associations, such as the Moy, Lee, and Chen families, served as community pillars and pseudo-governing bodies, providing support for each other and the residents. Although in its second iteration of home, These associations helped adjudicate neighborhood disputes, integrate new immigrants into their new home, and established Chinese language schools, essentially serving to fill any social welfare needs that the government could not or refused to. Operating adjacent to these associations were tongs, or businessman’s associations that helped adjudicate the neighborhood in the commercial sense, despite often being tied with organized crime. The Sunday Star described one example of their work, stating, “should a Chinese want to open a restaurant outside of Chinatown, his tong decides whether he would be situated too close to another member restaurateur. If the competition would not be too keen the association gives its blessing and even lends him money, if need be.” Racist policing practices capitalized on the crime associations of tongs for immigration crackdowns into the 1920s. An October 19, 1928 Washington Star stated, “a police campaign against Chinese who are in D.C. illegally [was] launched by the recent killings,” in reference to a murder in Chinatown that had occurred that year.

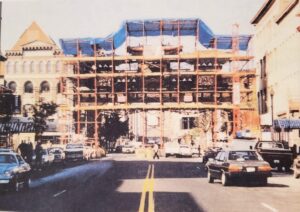

In 1931, the neighborhood was forced to relocate from Pennsylvania Avenue near John Marshall Place to its current location, centered around 7th and I Street as a result of the developing Federal Triangle and National Mall projects. It had been there for nearly 50 years. In 1932, led by an influential and large tong known as the On Leong Chinese Merchant’s Association, the community purchased and leased property on H Street to house the 11 businesses operating within their tong, effectively establishing a new Chinatown when a rival tong followed them soon after. The Sunday Star reported that the site of the former Chinatown was quickly destroyed to make way for new developments, “[presenting] somewhat the appearance of a village in Northern France after a German bombardment. Most of the old brick structures formerly occupied by the Chinese have been torn down to make way for new Government buildings.” This transition and resettlement was not without turbulence, as many were unhappy to house the Chinese community. White property owners on H Street unsuccessfully petitioned the government to keep the Chinese out, citing fears of deterioration of the neighborhood and property prices. The new Chinatown housed roughly 800 residents, making up 32 families. Immigration would continue to increase into the mid-1900s as the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed as a reflection of US-China relations during WWII.

Location: 5th and Eye St NW, on the street corner in front of the Chinese Community Church

Young Chinese Americans laid in a position between their new American lifestyles and the effort to maintain Chinese identity. In 1931, D.C.’s first Chinese school was founded, where students could learn Chinese customs and way of life following their American education in the day. However, racial attitudes and discrimination were the worst they had ever been, due to the divisions and fear caused by the Great Depression. Chinese Americans were markedly ‘colored’, and were therefore subject to heavy racialization. This would continue into WWII, where anti-Japanese sentiment led Chinese Americans to make heavy display of their patriotism and distinguish themselves from Japanese Americans. Some would hang flags, fashion identification cards, and wear emblems that signaled both their allegiance to the U.S. but also emphasize the positive relationship between the U.S. and China.

In the 1960’s, immigration quotas were expanded, and D.C.’s Chinatown, like many, experienced an uptick in population. By 1966, DC’s recorded Chinese population of first- and second-generation immigrants hovered around 3000. Because of the insularity and relative self-sufficiency of the community, the majority of the first generation immigrants would never learn English, while their children would have weak to no grasp of their parents’ mother tongue. The influx of new immigrants also marked the beginning of a dispersive effect, however, and Chinese shops and small communities began to form around the suburbs of D.C..

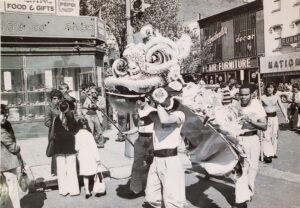

While this dispersion was underway, however, Chinatown would continue to serve as a community and cultural center for many Asian Americans in the DMV area, even as many moved to the suburbs of Maryland or Northern Virginia. Chinese New Year festival celebrations became one such opportunity for these diasporic groups to gather, and served as a cultural touchstone by hosting activities such as traditional costume shows, acrobatics, martial arts, among many others.

Many non-Chinese Asian American minorities also participated, demonstrating the neighborhood’s wide significance. D.C.’s Chinatown also participated in the national Chinatown tradition of playing street volleyball.

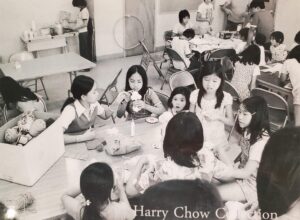

Neighborhood programs and institutions also helped inspire the lives of young people in Chinatown. The Chinese Community Church (CCC), founded in 1935, began offering services in Chinese in the early 1950’s and continues to do so to this day. The Chinatown Creative Workshop was one such example. It served as a program for new immigrant children to become quickly integrated into their community by teaching dance, art, and cultural classes. The program was largely successful and hosted anywhere from 30-50 children each year, but was ended in the 80s due to a lack of government funding. These programs laid in a delicate position between the wealth divide in D.C.: they did not have the money to be self-sustaining, yet were not poor enough to receive sufficient funding from the government.

In a 2003 interview for Small But Resilient: Washington’s Chinatown over the Years, childhood resident Wendy Feng noted “I think one of the reasons people initially sojourned or stayed in Chinatown was because they felt safe in Chinatown. And I think a part of it was the Anti-Immigration Act [of 1882]…that sort of gave people the excuse to really behave badly towards them. And so they felt that they have to sort of isolate themselves within Chinatowns.” Nevertheless, Chinatown had definitively established itself as a home and home base for both a new and old diasporic population. Businesses, community organizers, and schools shaped the space that provided for many.

Location: 8th and H Street

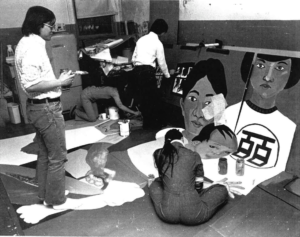

Standing on 8th and H Street, the view can be relatively unassuming. 8th and H Street was the location of the Jade Palace restaurant, where a large mural by Eastern Wind was hung for eight years.

Designed by member and resident artist Miu Eng, it aimed to depict a multi-generational Chinese American identity, and included imagery of traditional family values, food, and connections to a homeland. The mural was significant because it engaged a specific emerging identity: one of a young, original Chinatown made of Chinese Americans with a specific and enterprising political identity that came of age alongside the Civil Rights Movement. Chinese and Black solidarities had been growing the last decade, as political self-awareness had begun to rise both inside and outside the Chinese community.

Many projects, groups, and small organizations formed in this political upturn in Chinatown. Eastern Wind was a publication that served as both a newsletter and a Chinese American magazine for the DC area. While Chinese American in name, it aimed to engage all Asian American ethnic minorities, and often spoke on larger issues facing Asians and Asian Americans. Eastern Wind was described by member and long-time Chinatown resident Harry Chow as “idealistic, enthusiastic, and outspoken.” Run by college students, the publication was an activist and leftist space, and engaged issues facing both their specific locale, such as protesting the construction of the convention center, as well as a larger Asian American national discourse, exemplified in September/October 1975’s issue titled “The Immigrant Issue”.

Eastern Wind marked an important instance of the Chinese American community being in conversation with a greater national discourse. Voices that had been historically suppressed by language discrimination and access, positionality, and space were now highlighted in an important way that was given an important platform to speak for themselves and reckon with their own place. Its specific space-oriented focus on Washington D.C. also helped to parallel the concentrated Asian American movement on the West Coast. The same issue as above featured a letter titled “Eastern Wind Talks Back”, written in response to a racist Washington Post article, which featured this line:

“Our outrage at being ignored as long-time contributors to America is only compounded by the continued lack of sensitivity to the Asian community. We hope and demand that in the future The Washington Post and other newspapers exercise better judgement when writing about a community of which they are neither a member nor well informed.”

Political identity was becoming less and less insular, and Chinatown became a site of inquiry for the city as a whole. Chinatown was a major site of work for Lady Bird Johnson’s 1960s Beautification agenda. Believing the mental health of a nation was highly reliant on aesthetic beauty, Lady Bird Johnson aimed to use Washington D.C. as her “front yard” example of this broader nationwide effort. Chinatown became an experimental ground for a series of infrastructural improvements, including the installation of public art and an increase in greenery, amongst other changes. These issues were not merely approached as a cosmetic bandage on issues of racial inequality and redlining, but as a method of streamlining resources for improving overall quality of life: clean water, air, and environments. The degree to which this agenda contributed to the gentrification of the area that continues today is unclear, but not insignificant. The Beautification agenda operated heavily in Black neighborhoods as well as Chinatown, with Lady Bird Johnson herself appearing to promote her work in the public eye.

Chinatown was also impacted by the unrest following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in April 1968. Civil unrest affected the entire city, and residents reported rioting, burning, and looting of many businesses and storefronts. All businesses, including Chinese, were asked to close early out of respect. Harry Chow, longtime Chinatown resident, lived in the neighborhood through the unrest. His family ran a laundromat. As he recounts, a young woman entered the store warning that businesses on their Chinatown block were going to be destroyed. Another friend advised that they should place a sign reading “soul brother” in front of their store, signaling solidarity with the protestors. Their business was untouched throughout the night. Another business operated by Chinese immigrants was a grocery store in the historically Black Shaw neighborhood. The owners, close with the surrounding Black working-class community, also found their store untouched throughout the unrest. Windows and street fronts were marked with large X marks in soap to signify that the businesses were to be spared. Following the events of May 1968, however, the neighborhood was “essentially shut down for a week.” Many residents felt unsafe, hurt, and scared, with some citing the unrest as a reason to close their businesses, and move out of the city into the suburbs of Northern Virginia and Maryland. The population, already dwindling by the mid-60s, “didn’t know how to fit in.” Watch the full documentary here.

Location: 7th and H Street NW. Notice the Chinatown Friendship Archway, the iconic imagery of the neighborhood.

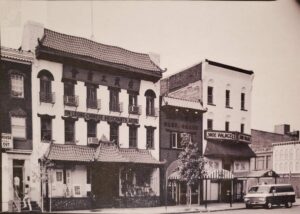

Into the late 1900’s, property prices in the neighborhood continued to rise, and it became increasingly difficult for residents to stave off developers and the tidal wave of gentrification. Local residents were offered large sums of money to buy out their property, especially to working class immigrant families. Chow described it as “enough to buy property in the suburbs, pay for college, and then some on top of that.” Many moved to the suburbs, and along with them, many of the amenities that sustained the distinct needs of the Chinese population – grocery stores, Chinese-speaking community services, and fellow Chinese American residents. In 2015, it was estimated that the Chinese population that remained in the neighborhood was as low as 300.

First generation elderly residents of Chinatown were hit the most hard by these changes. Wah Luck House, completed in 1982 and located on 6th and H Street NW, is the only remaining rent-controlled housing option for these residents, and the units are highly sought after. Many remaining residents are engaged in battles to stay where they are, and worry whether they’ll be able to stay in D.C. if Section 8 housing contracts evaporate.

Today’s Chinatown marks a very different neighborhood than the one that was first founded in the 1800s. The Chinatown Friendship Archway, built in 1986 and designed by Alfred Liu, is one example of this. Dually financed by the cities of Beijing and D.C., the archway marked solidarity between the two nations. Plans originally included an equivalent archway on the other side of Chinatown honoring the relationship between Taiwan and D.C., but was never completed.

Still, the archway’s highly Asiatic imagery serves as a landmark, and marks the neighborhood as visually Chinese. This is not unintentional: in 1986, a group of Chinese American community advocates formed the Chinatown Steering Committee. Working with the D.C. Office of Planning, they began a series of reforms that encouraged English-Chinese signage in the neighborhood. The Office of Planning writes, “enhancing Chinatown’s physical experience requires activating streets with Asian themed vendors and animating buildings with Chinese signage and storefront design.” This includes the zodiac-themed crosswalk markers, dragon adornments on Capitol One Arena, and many others. Notice, for example, the zodiac decorations on the crosswalk.

These crosswalk decorations serve as a good example to think further about the rest of the neighborhood. While clearly themed after the Chinese zodiac, it’s a superficial representation that serves only to appear Chinese without accomplishing much for the neighborhood itself.

In reflection, what does an ‘Asian theme’ really mean for the things that we know make Chinatown important today? The ‘themed vendor’ and ‘Chinese signage’ speaks nothing to the actual residential population as well as the now-dispersed Asian Americans who look to the neighborhood as a cultural touchstone. For example, many of the businesses now located in Chinatown are non-ethnic owned typical chain businesses, and are only markedly ‘Chinatown’ by the inclusion of phonetic spellings of their brand names in Chinese characters.

We must ask the question of what this really accomplishes for Chinese and Chinese Americans who look to and rely on this neighborhood. If the remaining Chinatown residents are facing eviction and aren’t being protected, the businesses aren’t Chinese-owned, and the visitors are not visiting ‘for’ Chinatown, what makes this neighborhood Chinatown besides nomenclature?

We can find the answer in history, in memory, and in this small but resilient community. While often considered a ‘dying Chinatown’, D.C.’s Chinatown is precious, storied, and home to many, even those who may not live there anymore.

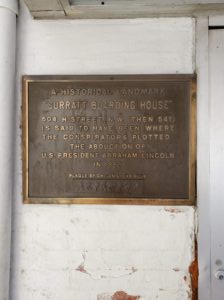

Surratt Boarding House

The Mary E. Surratt Boarding House, constructed in 1843, was the site of several meetings of the co-conspirators in the plot to assassinate Abraham Lincoln. Surratt herself was associated with Confederate sympathizers, and when put on trial for conspiracy, Mary Surratt became the first woman executed by the United States federal government. The space has since been returned to a commercial space, and houses a restaurant today with a plaque to honor its history.

Wah Luck House

Wah Luck House, located at 800 6th Street NW, is an important space for those who have remained in the Chinatown community. Built in 1982, it is one of very few remaining rent-controlled spaces, and houses the greatest density of Chinese residents that remain in the neighborhood.

Temple of Cun Yum

Also known as Guan Yin Temple, the Temple of Cun Yum is a Buddhist temple located on H Street NW. While small in size, the space is one of few religious sites left in the neighborhood and is known for its distinctive pink color and green roof. The interior houses a number of religious objects and spaces of worship.

Chinese Community Church

The Chinese Community Church (CCC) was founded in 1935 and has been a continually operating community staple ever since. Providing services in English and Cantonese, the church was key to helping early immigrants settle, find community, and gather together. They also house a number of community events, services, and programs that connect those from all over the DMV area, including the Chinatown Service Center. The CSC offers a number of programs, such as personal finance classes and English classes.

Click here to see citations. Special thanks to Harry Chow for photographs provided to the 1882 Foundation.