“Lives of Color: 1850-1900” – A Panel Discussion with the National Park Service

by Roberta L. Chew

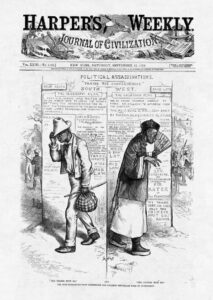

The second event held on September 29, 2015 of our series commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the 1965 Immigration & Nationality Act and the Civil Rights Movement featured participants from the National Park Service. The masthead on our 1882 Foundation website and 1882 Symposium Facebook page features two Chinese men who fought in the American Civil War, Joseph Pierce (left) and an elderly Edward Day Cohota (center). The two soldiers were among an estimated three hundred Asians and Pacific Islanders who fought on both sides of the conflict. They had come from twenty-five different countries to America. Some are hard to find and research because of their Anglicized names.

Carol Shively edited the new NPS publication titled, “Asians and Pacific Islanders and the Civil War,” one of a series of books issued in commemoration of the 150th Anniversary of the Civil War. Joseph Pierce was born in Canton. At age ten, he allegedly was sold for six silver dollars and brought to Connecticut by a ship’s captain, Amos Peck, and raised by his family. His Chinese name is unknown. He was given the name Pierce because Franklin Pierce was then president of the United States.

Responding to President Lincoln’s call for Union volunteers, Joseph Pierce signed on with Company F, 14th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry in July 1862. After only a month of training, he fought at the Battle of Antietam, the single bloodiest battle of the Civil War. He also fought at Gettysburg and Petersburg. After the war, Pierce returned to Meriden, CT, became an engraver, married and raised a family. In 1894, when the law required him to register as a “Chinaman,” he cut his queue and listed his birthplace as Japan. He never told his daughters he was Chinese.

San Francisco-born Irving Moy became interested in Corporal Joseph Pierce and researched him extensively. He traced Pierce’s genealogy and found his five great-granddaughters. Moy shared with them his research about their ancestor’s courageous past. They had known nothing of his true identity and military service. Irving Moy volunteers as a Jose ph Pierce re-enactor with Company F, 14th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry at Civil War commemorative events.

ph Pierce re-enactor with Company F, 14th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry at Civil War commemorative events.

Edward Day Cahota was another Chinese boy brought to New England by a ship’s captain, Sargent Day, on a ship named Cahota. In February 1864, Cahota enlisted in Company I, 23rd Massachusetts Voluntary Infantry. He fought in the Battle of Drewry’s Bluff near Richmond, Virginia, and again at the Battle of Cold Harbor where he saved the life of a badly wounded comrade. Cohota left the army, then re-enlisted repeatedly becoming a career soldier, despite marriage and family. Although he had served his adopted country for 30 years, he was denied U.S. citizenship. Cohota went to Washington, D.C., to appeal to his House representative and to a House committee. They looked in vain for a statute that would allow him to claim citizenship. Despite this, every evening an elderly Cohota unfailingly stood at attention at the lowering of the American flag at the veterans home where he lived during his final years.

Thanks to the efforts of Representative Mike Honda of California, some measure of recognition was finally achieved for these long forgotten soldiers when House Resolution 415 was adopted in July 2008. The resolution recognized and expressed appreciation for the courageous and loyal contributions made by soldiers of Asian and Pacific Islander descent during the Civil War, and honored by name two of them, namely Joseph L. Pierce and Edward Day Cohota.

On the panel with Carol Shively, Ted Alexander, National Park Service Historian at Antietam National Battlefield, provided additional insights and descriptions of Chinese in the both sides of the Civil War. “Most don’t know that a few hundred Asians served the Union cause in the Civil War,” said Alexander. “Even fewer know that Chinese lived in the south and some joined the Confederate Army.”

According to Alexandria, Chinese arrived in the south in the 1840s and 1850s. They had disembarked at the major southern ports – Baltimore, Charleston and New Orleans. Some moved inland to settle in places like Louisville, Kentucky, and existed in pockets of Chinese here and there in the south.

The Chinese were not numerous. They came in groups or individually. There was confusion over how to regard them. They were neither black nor American Indian nor white. Census designations varied. In some places they were considered “mulatto” or mixed race. The Chinese were most prominent in Louisiana, particularly in New Orleans, where they were classified as white. They were craftsmen – cigar makers, kite makers. Today’s famous French Quarter was once the site of Chinatown. Perry Lee, Jefferson Parish sheriff grew up in New Orleans’s Chinatown.

Chinese in the Confederacy included Siamese twins Chang and Eng Bunker who traveled with P.T. Barnum. They prospered and settled in Mt. Airy, North Caro lina where they owned two farms, slaves and married two white sisters with whom they had more than twenty children. Two of them – cousins – Christopher and Stephen Bunker, joined the 37th Virginia Cavalry Battalion a year apart. Christopher was at the July 1864 burning of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania under the command of Gen. McCausland. Chambersburg was the only northern town destroyed by Confederate forces. Wounded at Moorefield, West Virginia, Christopher was captured, sent to prison at Camp Chase in Ohio and later released to return home.

lina where they owned two farms, slaves and married two white sisters with whom they had more than twenty children. Two of them – cousins – Christopher and Stephen Bunker, joined the 37th Virginia Cavalry Battalion a year apart. Christopher was at the July 1864 burning of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania under the command of Gen. McCausland. Chambersburg was the only northern town destroyed by Confederate forces. Wounded at Moorefield, West Virginia, Christopher was captured, sent to prison at Camp Chase in Ohio and later released to return home.

Alexander also mentioned the Avegno Zouaves, a Confederate Louisiana unit with a mixture of nationalities. Their colorful uniforms with red baggy pants emulated the style of French colonial units called Zouave in North Africa. Chinese may have served with the Zouaves or they may have been Filipinos or mixed race Filipinos called “Manilamen.” These were originally Filipino sailors who jumped ship in New Orleans and settled in Louisiana’s bayous.

After the war, plantation owners brought Chinese to the South to replace slaves in the cotton fields and to build railroads in Louisiana and Texas. At a Chinese Labor Convention held in Memphis, Tennessee in 1869, Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest pledged $5000 to bring in 1,000 Chinese workers. However, Frederick Douglass railed against such a proposal, saying, “the Chinaman will not long be willing to wear the cast off shoes of the negro, and if he refuses, there will be trouble again.” Some Chinese initially came and worked in the fields. But they soon moved on, becoming craftsmen and opening small businesses such as grocery stores. The Chinese migrants did not become an alternative labor force on plantations, but for those who came and settled in places such as Cleveland, Mississippi, their legacy remains in the small businesses and communities they founded.

For more information, see Asians and Pacific Islanders and the Civil War, the Official National Park Service Handbook, 2015.