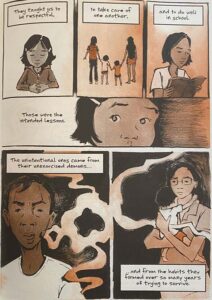

“And though my parents took us far away from the site of their grief… certain shadows stretched far. Casting a gray stillness over our childhood…hinting at a darkness we did not understand but could always feel”

In this beautifully illustrated memoir titled, The Best We Could Do, Thi Bui tells the story of her family’s journey of fleeing Vietnam and migrating to the United States. During the initial draft of writing this book, she felt that it came off as too ‘academic,’ and thought of alternative ways to relay history in a relatable manner. As a result, Thi learned to draw comics. This graphic memoir embarks on the complicated task of trying to tell a comprehensive story about war, family, migration, and loss.

As a child of an immigrant family, I deeply resonated with the narrative Thi drew of her relationship to her own family. Thi recalls growing up with Bô, her father, looking after her and her brother Tâm while her Má and her older sisters were at school. Thi vividly remembers the fear she had while growing up in that household such as the fear of when her father would lose his temper or the terrifying stories he would tell them regarding the supernatural. What becomes evident is the lack of comfort and safety that Thi felt during these moments of her childhood. However, as Thi grows older and later becomes a parent, she feels the need to understand how and why her parents are the way they are. As children of immigrants (in Thi’s case, refugees), we often interpret our family’s coldness/distance from us as a fundamental part of who they are rather than something they were constructed to be.

As Thi delves into the past experiences of her family, we learn of Bô’s difficult childhood and his fraught relationship with his abusive father over the years. Moreover, we hear about the tumultuous environment of Vietnam during a period of massive upheaval with the surrender of the Japanese, the invasion of the French, and infighting between the Northern region and Southern region of Vietnam. Additionally, we later learn how Má’ experiences multiple instances of her babies dying after birth. While I want to stress that her parents’ past does not minimize the trauma she later experiences growing up, I think this memoir reminds us that these two concepts can co-exist: their parenting was not perfect (and can be harmful at times), but they are also humans that experienced a lot of hardship in their life.

One of the reasons I was drawn to reading this memoir was because Thi utilizes oral history interviews. As a graduate student studying oral history methodology and theory, I recognize that oral history is an imperfect practice. Interviews are often riddled with mistaken recollections, lapses in memory, and other related issues. Even Thi mentions the difficulty of interpreting her family’s oral histories and reconciling it with the dominant narrative told about the Vietnam War. Regardless of its imperfections, I still stress the uniqueness and importance of oral histories as a way to counter hegemonic narratives of war and atrocities.

Another main reason that I was drawn to this novel is that Thi puts into practice what I have been wanting to convey as a burgeoning historian myself: how can we present history in a way that can reach a general audience rather than these discussions being confined to insular spaces of academia?

To finish off this post, one persistent question came to mind when reading this memoir – What are the survival mechanisms immigrant families deploy when they live in the wake of war?

In my mind, the answer is in the title: the best they can do.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Hannah Ku is an intern at the 1882 Foundation. She is a master’s student studying Asian American history, public history methodology, and critical adoption studies at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. She graduated from the University of Pittsburgh with a BA in History, a minor in Chinese, and a certificate in East Asian Studies.