“Every adoption requires a family to be broken apart. Yet, you never hear about that grief”

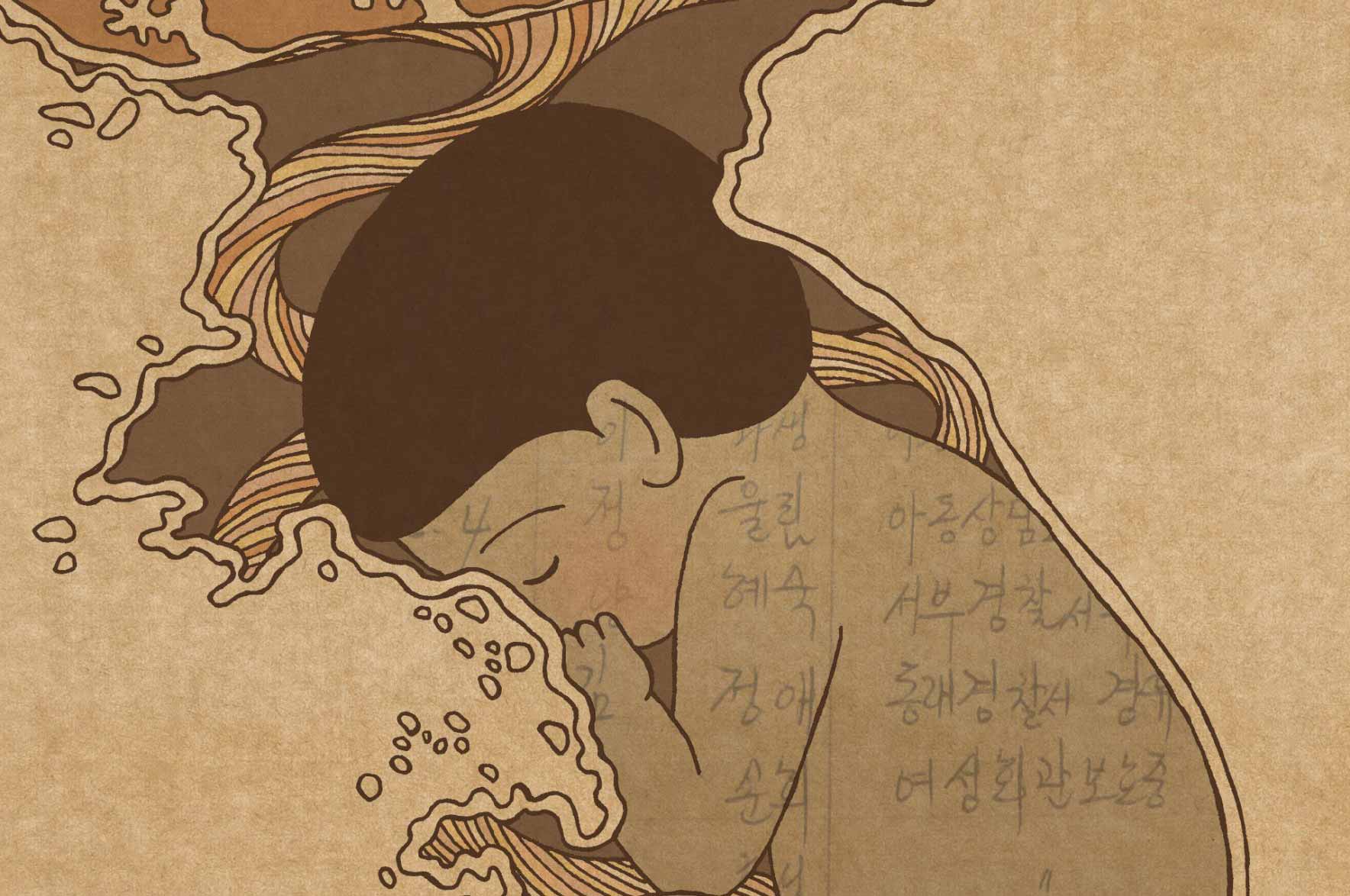

Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom in Palimpsest: Documents From a Korean Adoption illustrates the process of investigating her adoption documents to better understand her origin story. Lisa is a Korean transnational adoptee, illustrator, cartoonist, graphic designer, and adoptee rights activist who beautifully captures the multi-faceted and difficult experience of being a transnational and transracial adoptee within this graphic novel. When becoming pregnant with her first child, Lisa began to question further about her origin story and she thought about her own mother’s experience carrying her. For example, Lisa wondered if her mother was similarly scared or if she was shocked.

Before diving into the crux of the graphic novel, she juxtaposes two definitions from the Cambridge Dictionary: palimpsest and adoption.

Palimpsest:

A very old text or document in which writing has been removed and covered or replaced by new writing.

Adoption:

The act of legally taking a child to be taken care of as your own.

There is a common conceit that the process of adoption produces a clean-slate for the child when they are adopted into a new family. In this sense, adoptees are completely erased of their previous history, kinship ties to their birth family and birth country. However, in Palimpsest, Lisa draws an entirely different narrative regarding the lived experience of adopted children. Contrary to this “clean-slate” narrative, Lisa reveals that the system of adoption is inherently structured by loss and grief.

Lisa describes this loss through her own experience of holding onto her birth culture and roots as she was growing up. While she tried to hold onto “being as Korean as she could,” she began to lose pride in her birth culture as she experienced racist remarks at school and in public. However, after the birth of her children, she decided to search again for her Korean roots. Lisa expresses the frustrating process of delving into her adoption documents since she was, “completely dependent upon other people’s goodwill, and [she’s] constantly trying to keep [her] hopes down to protect [her]self from disappointment.” Through this tiresome process, Lisa reveals the dark underside of the transnational adoption network. While normally we give so much legitimacy to “official” documents as “true” origin stories, Lisa uncovers a multitude of inconsistencies within these records. Moreover, she is stating the uneasy truth that no one actually wants to hear about supposedly benevolent adoption networks: the process of adoption is a legal and illegal form of economic exchange that relies upon the vulnerability of birth mothers and the exploitation of children.

As someone who was transnationally adopted, this text deeply resonated with me. I rarely find material about adoption written BY adoptees themselves. Oftentimes, it feels quite lonely to be an adoptee. Adoptees do not neatly fit into an identity category, which makes it hard to relate or identify to others who are not in our position. Our complicated feelings about our adoption are typically disregarded by others as inconsequential and at times ungrateful to our adoptive parents. As Lisa puts it, “Our yearnings for our original families and our pursuits for answers about severed biological ties are dismissed as only of interest to adoptees with mental issues, misfits, people who haven’t ‘successfully’ attached, people not capable of receiving the love offered to us.”

While Lisa is speaking from her own experience as a Korean adoptee and about the Korean adoption process, her work is important and so incredibly meaningful to adoptees everywhere. Not every adoptee experiences the same journey, but her description made me feel less alone in my struggle of reckoning with my past.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Hannah Ku is an intern at the 1882 Foundation. She is a master’s student studying Asian American history, public history methodology, and critical adoption studies at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. She graduated from the University of Pittsburgh with a BA in History, a minor in Chinese, and a certificate in East Asian Studies.