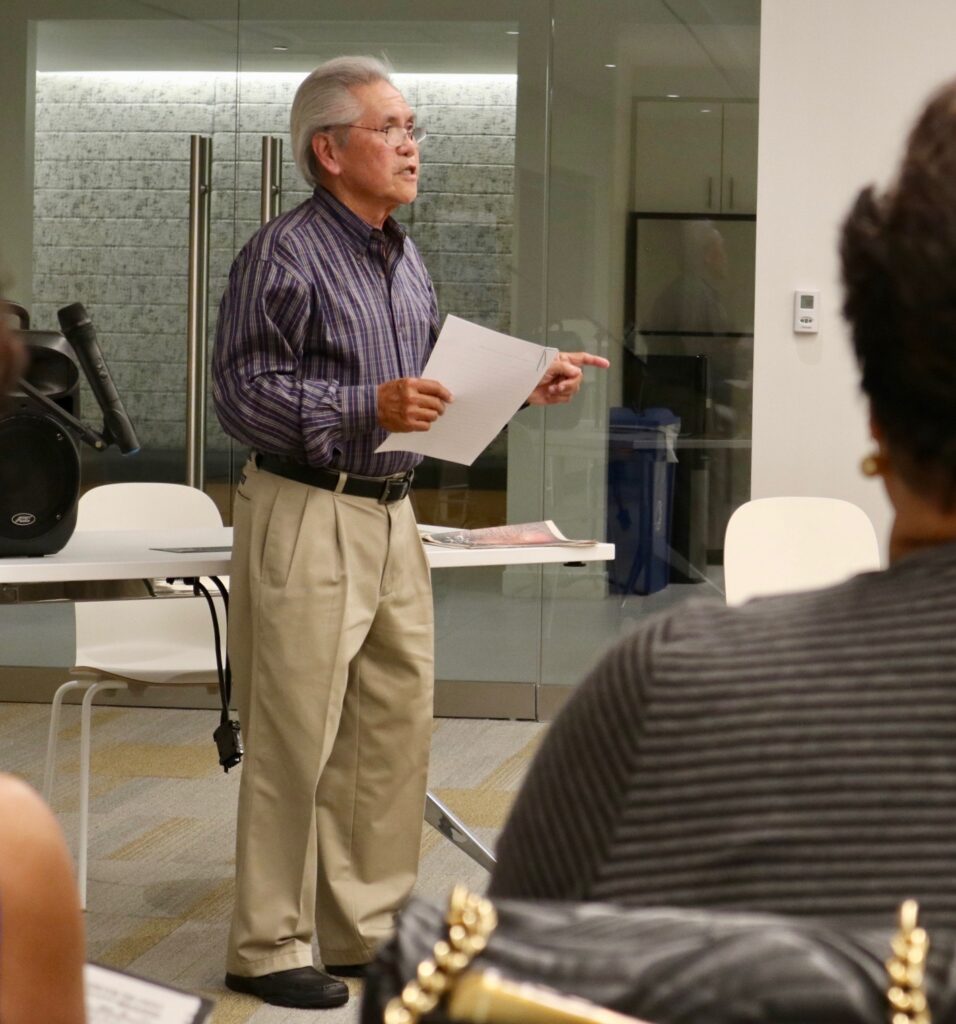

The September Talk Story featured several Chinese-Jamaican identifying speakers, who came to share their varying experiences growing up Chinese or part-Chinese in Jamaica, as well as their unique pathways to adult life the U.S.

Carol, the daughter of a married Chinese couple who immigrated to Jamaica, gave an overview of the history of Chinese migration to Jamaica, as well as various social and legal barriers that immigrants faced there. She discussed Jamaica under Britain’s rule for over three hundred years, how the abolition of slavery in the mid-nineteenth century resulted in a demand for coolie labor that Chinese laborers from the Hakka region filled, and discussed how Chinese culture encouraged immigrants to take on ethnically Chinese wives over non-Chinese ones, if they could afford to. Chinese immigrants were exploited in their labor contracts, the terms of which were often not met. Carol noted that by 1911, Chinese immigrants and their descendants comprised .3% of the population, but nevertheless faced claims by other racial groups that they were “taking over,” which explained the government’s first restrictions on Chinese immigration in 1905. Later generations of Chinese in Jamaica were very successful as shopkeepers and grocers, including Carol’s parents, who owned a hardware business in St. Thomas.

Many Chinese and part-Chinese children were sent back to China to be educated during their formal years to develop a strong Chinese identity, including the uncle of Suzanne and David, who always hosted the family for Chinese New Year.

One of the major themes the speakers touched on was ‘racial othering’. Two of the speakers were ethnically Chinese, and three were multiracial, Chinese-Jamaican siblings. When questioned, our multiracial speakers said that they did not feel like there were any social benefits or consequences to being biracial in Jamaica, and that only mixed-Chinese boys who were sent to China to be educated faced discrimination by Chinese society. Suzanne and her sister noted that many people referred to them as “Miss Chin,” a derogatory term commonly used to describe Chinese-presenting Jamaicans, but noted that, “my maiden name was Chin so I kept wondering how they knew my last name!”

Ken, who was raised in Jamaica as the son of a Chinese immigrant father and third-generation Chinese Jamaican mother, disagreed about the impact of racism against the ethnic Chinese in Jamaica. He noted that when he was growing up, people made fun of his appearance and teased him about “eating dog,” and other stereotypes about Chinese culture. He insisted that the teasing during his childhood gave him such a tough skin that he isn’t bothered by the racism that he encounters in the U.S. today.

Another major theme was migration and family separation. Despite the fact that all of the speakers were raised in Jamaica, none of them lives there today; everyone immigrated to the U.S. and Canada. Ken’s wife got a job in Washington, D.C. at the United Nations office, which she applied to on a whim but which allowed them to escape the unrest in Jamaica during the 1970s. Likewise, Carol left Jamaica in 1962, the year it gained independence, and went to college in New York City, where she met her American husband.

While the specific conditions and local climate in Jamaica were unique, it’s apparent that many Chinese-Jamaicans faced similar types of discrimination as Chinese immigrants to the U.S., especially in terms of coolie labor conditions, raising multiracial families, and reconciling cultural traditions that are at odds.