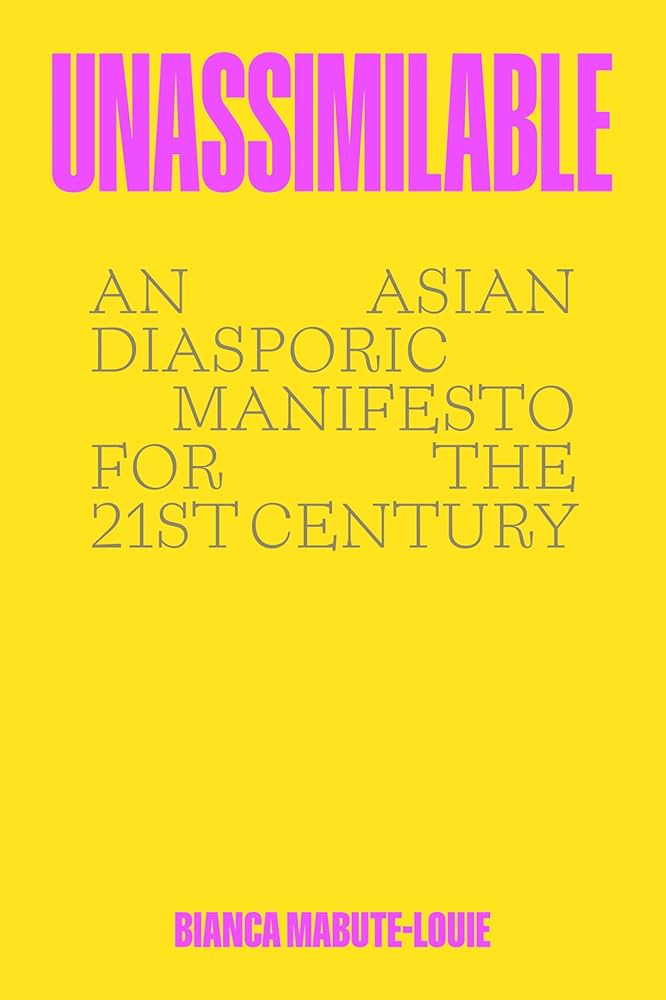

How do Asians in the United States create a sense of belonging and liberation in a nation structured by white supremacy, colonialism, and anti-Black violence? Sociologist, educator, and activist Bianca Mabute-Louie explores this central question in her powerful memoir-manifesto, Unassimilable: An Asian Diasporic Manifesto for the Twenty-First Century. Combining her personal narratives and sociological inquiry, Mabute-Louie introduces “unassimilability” not as a deficit, but as a political and cultural stance—a refusal to conform to the demands of the American empire and a call to build alternative forms of belonging rooted in solidarity, justice, and care. She advocates for the term “Asian Diaspora” over “Asian American” to reflect the global and historical complexities of migration, and to shift away from U.S.-centric narratives of identity. Framed as both a memoir and a manifesto, the book interweaves Mabute-Louie’s life experiences with deep reflections on race, religion, gender, queerness, and imperialism, ultimately offering a bold and radical vision to build collective belonging alongside and among each other.

The structure of the book is chronological, tracing the author’s life from her childhood through adulthood as an individual from the Chinese/Asian diaspora who has lived in the United States. Each of the eight chapters explores a facet of diasporic life—assimilation, racialization, anti-Blackness, religion, gender, mental health, education, and migration—through both personal and collective lenses. In the first chapter, Mabute-Louie unpacks the historical concept and label of Asians as “unassimilable” and reclaims the term as a marker of resistance against assimilation in an anti-Black, colonial nation-state. The second chapter examines two common stereotypes of Asian Americans as perpetual foreigners and model minorities, and how these narratives restrict individual agency among the Asian Diaspora and reinforce white supremacy. Chapter three directly tackles anti-Blackness within Asian communities and calls for cross-racial solidarity in achieving collective liberation from empire and colonialism, encouraging the Asian Diaspora to see the struggles of other communities of color as inseparable from their own.

Subsequent chapters challenge dominant frameworks around religion, gender, and mental health. Chapter four critiques the role of Christianity in upholding colonial power, while also acknowledging its potential as a site for decolonial resistance and spiritual reimagination among Asian diasporic communities in the US. In the next chapter, Mabute-Louie highlights the experiences of queer, femme, and gender-nonconforming Asians in the Diaspora, questioning heteropatriarchal norms both within families and broader diasporic institutions. In chapter six, she later discusses intergenerational trauma, war, and silence within Asian immigrant households, reframing mental health not as an individual failure but as a collective opportunity for healing. The seventh chapter underscores the transformative potential of ethnic studies and storytelling as tools for empowerment and raising consciousness. In the final chapter, Mabute- Louie places Asian diasporic struggles within the broader global context of U.S. militarism, refugee resettlement, and settler colonialism, and critiques narratives that erase the violent histories behind migration and refugee resettlement.

Unassimilable is especially relevant to the Asian American community for its refusal to separate Asian American identity from colonialism and US empire and local complicity with white supremacy. Rather than simply celebrating cultural difference or assimilation, Mabute-Louie calls for a more radical transformation: one that requires deep interrogation of racial privilege, anti-Blackness, and settler complicity within the Asian Diaspora. Her concept of “relational liberation”—a framework grounded in truth-telling, mutual care, and intersectional

and interracial solidarity alongside one another —pushes readers to reimagine community beyond the bounds of nationalism, capitalism, or cultural pride. The book makes a significant contribution to Asian American scholarship and literature by expanding the scope of what Asian

identity can mean and what it must confront, offering an urgent intervention for a community often left to navigate harmful stereotypes in silence.

I found Unassimilable to be deeply moving, intellectually rigorous, and politically generative. Its balance of storytelling, academic insight, and actionable vision makes it a standout text in the growing field of Asian diasporic/Asian American studies. What struck me

most was Mabute-Louie’s vulnerability in sharing personal moments of contradiction, growth, and re-education—experiences that mirror the internal work many in the Asian Diaspora must do to unlearn dominant narratives and build coalitions across differences. At the same time, she never loses sight of the systemic forces that shape the experiences of the Asian Diaspora. This dual attention to individual and systemic realities gives the book its emotional and analytical power.

I highly recommend Unassimilable to anyone seeking a deeper understanding of the complexities of Asian diasporic identity, particularly in relation to race, gender/sexuality, empire, and liberation. It is an especially important read for those in the Asian Diaspora

grappling with inherited traumas, discrimination, and the desire for collective belonging and healing. In a moment marked by increased discrimination and state oppression against marginalized communities, Mabute-Louie’s manifesto is both a refusal as well as an invitation:

to reject assimilation into violent systems and to build a new world together, one rooted in care, history, and possibility.

Written by Sraavya Chintalapati, 2025 Summer Intern, University of Texas, Austin ’24