On July 16th, I attended Washingtoniana’s Researching “Red Summer” at Woodridge Library. Archivist Derek Gray from the DC Public Library, a longtime partner of the 1882 Foundation, led the session and detailed various Red Summer resources. Though Red Summer is not directly related to Chinese Americans, the 1882 Foundation is interested in the databases available to research forgotten histories and to find primary source materials. I will first explain what Red Summer is and where to learn more, ending with why I believe researching Red Summer is ultimately significant to the Chinese American community.

Red Summer

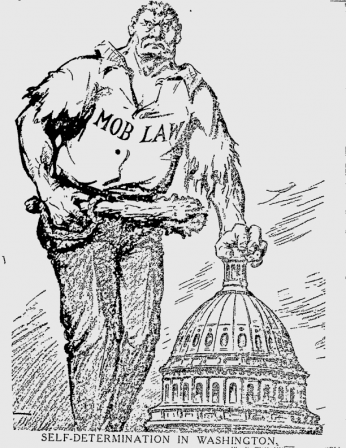

What is Red Summer? The term refers to the summer and fall of 1919 when white supremacists attacked blacks in cities across the US. The Washingtoniana event marks the 100th anniversary of these race riots. The event focused on Red Summer in DC, which lasted from July 19th to July 24th. It started because of a rumor that a black man sexually assaulted a white woman, who was also the wife of a Navy officer. Veterans, still in uniform from World War I, started attacking any African Americans they saw. The police did not intervene. The black community began fighting back, though this was not the case in other cities. There were a total of 15 deaths– 5 black people and 10 white people– making DC the only city with more white deaths. In other parts of the US, such as Chicago, the riots lasted much longer with many more casualties.

Resources: Newspapers

Newspapers are one main source to learn about Red Summer. Newspapers.com, the DC Public Library Special Collections, and Washingtoniana are all great databases. Specific African American newspapers include the Washington Bee, Washington Tribune, and the Chicago Defender. The Washington Bee is a more militant and radical newspaper than the Tribune– its slogan was “Honey for our friends, stings for our enemies.” The Bee was edited by William Calvin Chase, who believed that an interracial world would never work and hated W.E.B. Du Bois and the NAACP. However, he changed his mind once he saw the NAACP tackling the issue of segregation. After Chase’s death in 1922, the Bee closed, and the Tribune took its place.

Currently, the Washingtoniana facility on Connecticut Ave is closed for maintenance issues, but archival collections are at the Georgetown Library Peabody Room. The collection is also digitized and can be accessed with a DC Library card. (P.S. You do not have to live in DC to sign up for a free DC Library card!)

Resources: Letters

Letters are a great source for firsthand information about Red Summer. Below I have listed 5 collections.

1) Archibald Grimke Papers from Howard University

Archibald Grimke’s July 1919 correspondence to NAACP branches across the US reveal mass confusion. People wanted to know what was going on in DC, whether or not the DC NAACP needed help, and if the assault on the white Navy officer wife was really true. Other NAACP chapters pledged to assist the DC NAACP.

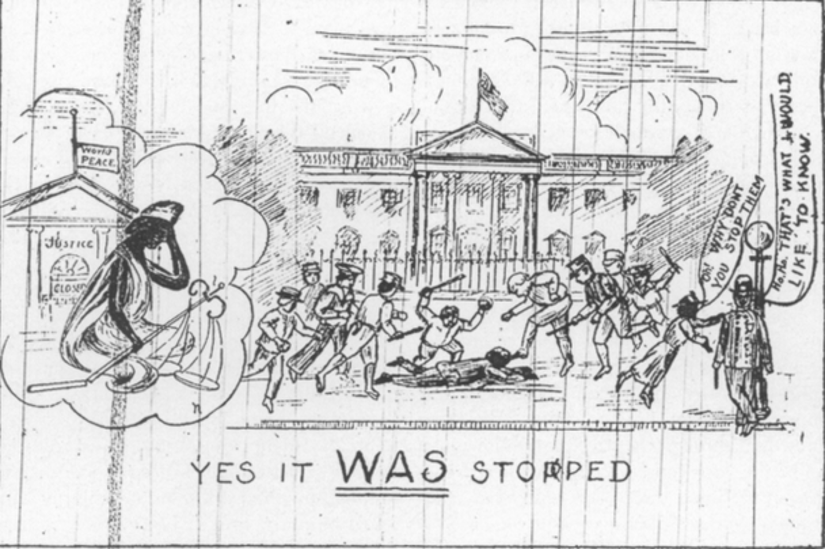

2) NAACP records from the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress maintains the largest collection of NAACP records, making it an incredibly valuable resource for researching DC history. The records include correspondence, telegrams, and reports of police brutality. One reporter was named Neval Thomas. He was on the streets during the riots in DC, directly reporting to Grimke. Thomas was also part of the DC NAACP delegation that met with Commissioner Louis Brownlow and Police Chief Raymond Pullman. Brownlow and Pullman refused to provide protection to African Americans and told Thomas that it was up to the NAACP to make sure blacks do not fight back.

Derek Gray shared a gut wrenching letter he found in the NAACP records. A 17 year old Francis Thomas wrote to the DC NAACP, describing how he was beat on a streetcar and thrown out the window. He had to crawl home. Gray could see his handwriting trail off due to his injuries. In fact, he does not even finish the letter because he loses consciousness.

3) James A. Cobb Papers from Howard University

Cobb was part of the DC NAACP’s legal defense team. Because of Cobb, George Dent, an African American prosecuted for attacking a white man, was found not guilty by self defense. Although no white rioters were prosecuted, the legal team was able to get reduced or dismissed sentences for almost all the black men arrested in Red Summer.

4) Woodrow Wilson Papers from the Library of Congress

The NAACP sent telegrams to President Woodrow Wilson, and he ignored them.

5) Mary Church Terrell Papers from the Library of Congress

Mary Church Terrel wrote about the aftermath of the DC riots in her July-Sep 1919 Correspondence Series.

Resources: Published Sources + Photos

Derek Gray recommended two books about Red Summer: 1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back by David F. Krugler and Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America by Cameron McWhirter.

For some reason, there are no pictures of Red Summer in DC, though there is photo documentation in other cities. When asked why, Gray responded, “Evidence that is incriminating has a funny way of disappearing.”

So What?

When I came home from this event, my parents asked, “What does this have to do with the 1882 Foundation? We thought 1882 was about the Chinese?” I tried to give this speech on solidarity, but if I’m being honest, I don’t think I did a good enough job for my parents to understand. So this is my do-over.

History repeats, and history rhymes. Red Summer happened in part because all the soldiers were returning from World War I. In American history, there is always an increase in violence after wars, whether it is Red Summer or lynching after the Civil War. In fact, after World War I and World War II, black men in uniform were specifically targeted by lynching. Derek Gray shared that his family member was an African American soldier who fought in World War II. Upon returning home, he found that he was treated worse than German POWs. German POWs– the enemy– were allowed to go into restaurants and eat, whereas he was mocked and attacked by the very people he fought for. This reminds me of Japanese Americans in World War II fighting, translating, and playing critical roles for the US while their families were forced into internment camps.

At the Washingtoniana event, an audience member remarked that race riots seem to be about property. Gray agreed, adding that violence is often tied to economic progress and equality. In the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot in Oklahoma, whites burned and destroyed a prosperous black neighborhood. The same thing rings true for Red Summer in DC– blacks were trying to do well, which infuriated white people. Another audience member noted that this can be compared to gentrification today, whether that is in predominantly black neighborhoods or Chinatowns across the country. Certainly, gentrification can be seen as a sort of violence against our most vulnerable.

Last year, the US commemorated the 50 year anniversary of the 1968 riots across the country, particularly in DC and Chicago. Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated, and DC was on fire. Literally. The concept of police brutality is often traced back here, but of course we can go back further to Red Summer in 1919. A few more steps back, and we’re in 1877, when federal troops were removed from the South and African Americans faced widespread violence, much like how the police force’s refusal to intervene in Red Summer caused the brutality to continue for far longer than it should have. This year is the 400 year anniversary of the slave trade in America– indeed, we can trace the roots of police brutality all the way to 1619 and conclude that America was founded on the abuse of black bodies.

But this violence doesn’t happen in a vacuum. America isn’t black and white– Chinese Americans have been here since the Civil War. This sentiment against the “other” reflects in the Chinese massacre of 1871, the Rock Springs Riot in 1885, the murder of Vincent Chin in 1982… We cannot ignore violence against African Americans because that violence is symptomatic of something that affects both our communities. We cannot allow our communities to be pitted against each other, as the model minority myth tries to do, because we are stronger together. Because the fight for a more just America starts with all of us.